“Hacking” is probably the best-known type of cybercrime, so I want to write a bit about it, from two perspectives: terminology and law.

Terminology is important because we really do not have settled terms in this area. As I suspect most people know, hacking is an ambivalent term: Historically – twenty, thirty, even forty years ago – the term “hacker” denoted someone who was intelligent, creative and resourceful and who “hacked,” i.e., explored computers and computer systems to see how they worked and how one could “access” (more on that in a minute”) a closed system. Hacking was an intellectual exercise, a constructive exercise because what someone learned by hacking often helped improve how computer systems functioned.

The terms “hacker” and “hacking” then went through an intermediate stage, one in which they began to take on negative connotations. “Hacker” began to become synonymous with “intruder,” or “burglar” (since burglars “break in” to places where they are not supposed to be). During this period, distinctions arose between “white hat hackers” (who engaged in hacking as a constructive exercise) and “black hat hackers” (who hacked for illegitimate reasons). There was also (still is, I guess?) the notion of the “grey hat hacker” whose activities fell in between, were a mix of constructive and illegitimate.

When I speak on cybercrimes, I sometimes use the term “hacker” and sometimes get grief for doing so because the term necessarily encompasses all three categories. I get grief (when I do) from people who point out that hacking is not always a “bad” thing and, historically, began as a “good” thing. I do not disagree. I simply explain that I need a term to use to refer to people who break into systems, and hacker is all I have.

And I think the notion of white hat hacker may be declining, at least in the popular consciousness. I think that, for many people, “hacker” has become synonymous with “criminal.”

Why is that? I think it’s due to an interaction between law and how computer technology evolved over the last two decades or so. As far as I can tell, the concept of hacking as constructive intellectual exercise prevailed pretty much unchallenged when computers were mainframes and even after they began to evolve into smaller versions, precursors of the desktop PC. The concept of “black hat hacker” emerged and began to dominate with the proliferation of desktop PC’s for at least a couple of reasons. One was that the attendant development of the Internet made it possible for a lot more people to be able to explore computer systems; and many of them were not motivated by the intellectual curiosity that prompted the original hackers to explore computer systems. The other reason is that as desktop PC’s (and analogues) proliferated, businesses and other likely targets of financial crimes came to rely upon them; this, of course, created an incentive for people to “hack” for purely criminal purposes.

Okay, that’s a brief history (hopefully fairly accurate) of hacking as terminology. Now I want to talk about law and hacking.

The U.S. federal government, every U.S. state and many other countries have laws that make “hacking” illegal. How do they do this? They do it by making it a crime to “access” a computer or computer system without being “authorized” to do so. These statues will provide that it is a crime (of varying levels) intentionally (or knowingly) to “access” a computer, computer network or computer system (they do tend to use all three) without being “authorized” to do so. In the world of the law, this means that it must either be your goal (your intent) to gain access to a system without being authorized to do so, or you must do this knowing that you are not authorized to do so. (Acting intentionally is usually seen as more “wrong” than merely acting knowingly, but that is not always true – it depends on the jurisdiction.)

Okay, the crime popularly known as “hacking” consists of “accessing” a system without authorization. The “without authorization” part is pretty easy, conceptually, because it’s analogous to burglary (entering someone else’s property without their consent). Police find me in a house that does not belong to me; I broke a window to get inside and I have a pillowcase filled with stuff from the house. My entry is “without authorization” because (i) the owner of the house didn’t give me permission to enter and (ii) I clearly know that.

The problem is “access.” What does it mean to “access” a computer system? Hacking is analogous to burglary in that you do something you’re not supposed to do, but you do not physically enter a computer system. You do . . . something else.

The federal hacking statute (18 U.S. Code § 1030) does not define “access.” Many state statutes do, and they usually say something like this: “`Access’ means to approach, instruct, communicate with, store data in, retrieve data from, or otherwise make use of any resources of a computer, computer system, or computer network.” (Florida Statutes § 815.03).

There are very few cases that deal with what “access” is, in practice. The one that is most often cited is from Kansas: State v. Allen, 917 P.2d 848 (Kan. Sup. Ct. 1996). In the Allen case, the defendant was war-dialing – using a dial-up modem to repeatedly contact the computer system at the Southwestern Bell Company. If a dial-in connected with the Southwestern Bell system, he hung up. He was apparently exploring the possibility of connecting to the system and interacting with it, but never got that far. The Kansas Supreme Court threw out the hacking (unauthorized access) charge against him because it said he had not “accessed” the system: “Until Allen . . . entered appropriate passwords, he could not be said to have had the ability to make use of Southwestern Bell's computers or obtain anything. Therefore, he cannot be said to have gained access to Southwestern Bell's computer systems”.

Most of the time, “access” is not a real problem because the perpetrator (the “hacker”) does communicate with the system and usually goes further by copying or deleting data, say. Access becomes problematic when, for example, someone is port scanning a system. There is only one federal case on port scanning and that court, like the Allen court, said that it was not access . . . which means it may not be a crime. (It is also a crime to attempt to gain access, but I have not seen any prosecutions for that.)

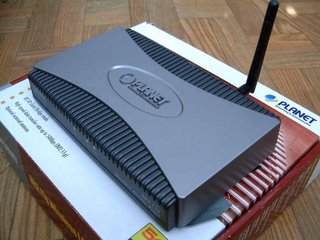

“Access” is particularly problematic when it comes to wireless systems: If I am in public, find an unsecured wireless network and use it (free-ride on it), have I illegally “accessed” that system? I don’t think so, based on the cases I note above and on common sense. Many people agree, but some disagree. Indeed, this post was prompted by an email I got today from a friend in Europe, where they are debating this.

I think the free-riding on a wireless system might well be prosecutable as theft of services (like stealing electricity) because you know you are getting something you paid for. On the other hand, though, there are intentionally free wireless systems out there, so you may not actually know that.

You would think law would have figured all this out by now, wouldn’t you?