I find it interesting, and instructive, that hate, or, more precisely, hate speech, is an issue that divides cultures as otherwise similar as the United States and Europe.

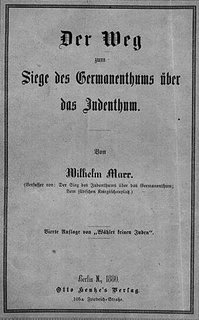

I find it interesting, and instructive, that hate, or, more precisely, hate speech, is an issue that divides cultures as otherwise similar as the United States and Europe.The image to the right is an example of hate speech, albeit a very old example of hate speech. It is a book (The Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism) written by a Wilhelm Marr, a German, and published in 1879. According to one source, Marr "coined the term `anti-Semitism' as a euphenism for the German Judenhaas, or `Jew-hate.'" The same source tells us that Marr's work "was a major link in the evolving chain of German racism that erupted into genocide during the Nazi era."

What, you ask, do hate and a nineteenth century purveyor of racism and hatred have to do with cybercrime in the twenty-first century? On the one hand, not much; on the other hand, maybe quite a lot, at least as the basis of an object lesson.

As I explained in a post last month ("Treaty"), the gaps and inconsistencies that currently exist in national cybercrime law provide a weakness, a vulnerability, cybercriminals can exploit to frustrate investigations and avoid prosecution. Those who are knowledgeable about cybercrime agree that this is a critical issue we must resolve if we are to deal effectively with cybercrime. The difficulty lies in how we resolve it.

One way would be to declare cyberspace to be its "own" jurisdiction -- to make it a "country" that exists separate and apart from the distinct territorial spaces that respectively comprise the nations of the world. This approach would then provide cyberspace with its own set of unitary laws and its own law enforcement agencies; some suggest the United Nations could take over the enforcement role. But while cyberspace might, and I emphasize might, someday become a distinct, sovereign nation, we are a long, long way from that. My sense is that none of the governments of the world are anywhere near ready to cede control of the activities their citizens conduct online to an external entity, regardless of its sovereign status.

So, that approach is not going to work any time in the foreseeable future. The other approach, as I explained in my previous post ("Treaty") is to see that countries of the world harmonize their laws so that (i) there are no gaps in criminalizing, say, hacking or the dissemination of malware and (ii) the laws of each country allow its law enforcement officers to assist officers from other countries in their investigations of cybercrime. This is, as I explained in my earlier post ("Treaty"), the goal of a treaty drafted under the auspices of the Council of Europe: the Convention on Cybercrime. In my earlier post I explained why I have some reservations about the extent to which the Convention on Cybercrime will succeed in harmonizing national cybercrime laws. That is not what I want to talk about today.

Let's go back to Wilhelm Marr and his anti-Semitic publications. The Convention on Cybercrime was drafted by representatives from the Council of Europe and from four other, non-Council of Europe countries: the United States; Canada; Japan and South Africa. See Council of Europe, Explanatory Report for the Convention on Cybercrime para. 304. When the Convention was being drafted, some of the European representatives wanted to include a provision requiring parties to the Convention to criminalize the use of computer technology to disseminate "hate speech," or the kind of "racist propaganda" Marr disseminated via the printing press. See Council of Europe, Explanatory Report for the Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime para. 4. The rationale was that "international communication networks like the Internet provide certain persons with modern and powerful means to support racism and xenophobia and enables them to disseminate easily and widely expressions containing such ideas. In order to investigate and prosecute such persons, international co-operation is vital." Council of Europe, Explanatory Report for the Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime para. 3. The United States, which played an influential role in drafting of the Convention, made it clear that if such a provision was included, the United States would not be able to ratify the Convention. See Council of Europe, Explanatory Report for the Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime para. 4.

The provision was therefore not included in the Convention on Cybercrime, but it later became part of an addendum to the Convention: the "Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime, Concerning the Criminalisation of Acts of a Racist and Xenophobic Nature Committed through Computer Systems" [hereinafter, "Protocol"]. The Protocol essentially requires the nations that sign and ratify it to adopt laws criminalizing the use of computer technology to disseminate "racist and xenophobic" material. Racist and xenophobic material is defined as "any written material, any image or any other representation of ideas or theories, which advocates, promotes or incites hatred, discrimination or violence, against any individual or group of individuals, based on race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin, as well as religion if used as a pretext for any of these factors." Protocol, Article 2(1).

This brings us back to Wilhelm Marr. The Protocol is specifically designed to prevent the Internet's being used to disseminate ideas such as those Marr put forth in the book noted above and other, similar efforts.

The notion of outlawing racist or hate speech is far from new. The German Penal Code has for years made it a crime to distribute "propaganda" that glorifies or otherwise supports Nazi ideals or the ideals of any other organization that has been declared to be unconstitutional by the German Federal Constitutional Court. German Penal Code Section 86. Other countries have similar laws, though they may differ somewhat in terms of the precise nature of the speech they prohibit.

The United States has never criminalized hate speech and almost certainly could not do so.. The First Amendment states that Congress cannot adopt any law "abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press". We can, as I have explained elsewhere, criminalize a few, very narrow categories of speech, but those are exceptional circumstances. We cannot outlaw hate speech (the Protocol's racist or xenophobic speech) because doing so would be criminalizing "pure" speech, not, say, the act of victimizing a child to create child pornography and then publishing that material on the web on in print. Child pornography is speech, but it is also something more; it is speech that memoralizes the victimization of a human being, of a child. We can, therefore, constitutionally criminalize child pornography because we are outlawing the infliction of physical and emotional "harms" on a person to create a particular category of speech, not "speech," as such.

I'm writing about this topic today because I'm writing a paper on a related topic (defamation online) and in the course of my research I discovered a provision that was proposed for inclusion in the Model Penal Code. The Model Penal Code was published in 1962, the product of many years of effort by members of the American Law Institute. It was intended to reform the then-existing state of criminal law in the United States. At that time, our criminal law was based on traditional English common law and was, as a result, antiquated in many respects. The drafters of the Model Penal Code wanted to update our criminal law by simplifying arcane and unnecessarily complicated rules that had evolved over the centures and by addressing issues that had not been a concern at common law. The therefore published a set of model laws -- the Model Penal Code -- that were intended to act as guides primarily for state legislatures, though the Model Penal Code has also had some influence on federal criminal law.

What I found interesting is that in an early draft the authors of the Model Penal Code proposed creating a new crime: "fomenting group hatred." It consisted of disseminating "any derogatory falsehood, with knowledge of the falsity" for the purpose of "fomenting hatred" against "any racial, national, or religious group". I find the provision interesting because it reminds me of the language in the Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime.

Unlike the Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime, however, the provision on "fomenting group" hatred" was never adopted . . . by the drafters of the Model Penal Code or by any U.S. state. In the commentary for the proposed provision, the drafters of the Model Penal Code explain why, at this point in time, anyway, they believed it could survive First Amendment challenges. They seem to have changed their minds later, though, and so did not include it in the final version of the Model Penal Code. As far as I can tell, it has gone unremarked and unnoticed ever since.

I mention the provision not because I believe it should have been included in the Model Penal Code. I think it should not because, unlike those who crafted it, I think it clearly could not survive First Amendment challenges. It would criminalize speech, pure speech . . . speech many would find to be hateful, repulsive and with no redeeming social value. The fundamental premise of our First Amendment, however, is that we, in the United States, do not criminalize speech because we do not like it, because it makes us uncomfortable, because it distresses others to the point that it can legitimately be characterized as inflicting a psychic assault on them. As a society, we believe in the "marketplace of ideas," the notion that the best ideas, the best beliefs, will triumph in a free, transparent discourse encompassing all views, however marginal they may seem.

That perspective makes sense to me . . . perhaps because it is the "right" perspective, or perhaps because I am an American and, as such, grew up with the notion that this is how things should be. I know other countries view hate speech differently. I have tried very hard to understand the premise that, for example, hate speech constitutes an assault, a psychic assault of the type I noted above. I have tried to understand the premise that hate-speech-as-psychic-assault is indistinguishable from the physical assaults every society criminalizes . . and I have failed. I am afraid I cannot, and never will be able to, see an equivalence between words -- mere words, mere speech -- and a physical attack on someone.

And that brings me back to the point of this post: The fact that Americans and Europeans (many Europeans, anyway) can view hate speech so differently illustrates the difficulties we will face, I think, in attempting to harmonize national penal laws so they consistently, and globally, address the problem of cybercrime. Law, especially criminal law, is inextricably bound up with culture, which is and will remain -- at least for the foreseeable future -- a parochial phenomenon, a product of local history and experience. I suspect the parochial nature of our national cultures is one reason why no one wants to "internationalize" cyberspace -- to turn it into a separate legal "place." We fear the loss of control, the loss of identity that would ensue.

It will be interesting to see how we work out the difficulties involved in retaining our national cultures while harmonizing our national penal laws to address cybercrime.

No comments:

Post a Comment