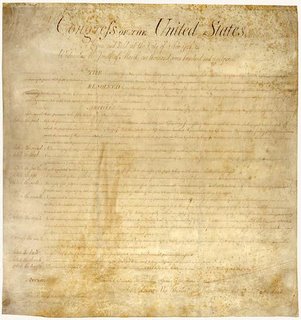

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees that "the right of the people" to be free from "unreasonable searches and seizures" shall not be violated.

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees that "the right of the people" to be free from "unreasonable searches and seizures" shall not be violated.A long time ago, the U.S. Supreme Court held that this amendment (unlike, say, the Fifth Amendment) applies only to searches and seizures that are conducted either (i) in the territorial United States or (ii) outside the United States against U.S. citizens. Under this interpretation of the Fourth Amendment, therefore, it does not violate the U.S. Constitution for U.S. law enforcement officers to search and seize property that is located outside the U.S. and that belongs to someone who is not a U.S. citizen.

I have some reservations about this interpretation of the Fourth Amendment as it applies to real-world searches, but it becomes especially problematic when we get into searches and seizures that involve networked computers. To illustrate what I mean, I want to use an investigation (and prosecution) that occurred several years ago.

In this case, businesses around the U.S. were being attacked by anonymous perpetrators whose favorite tactic was to gain unauthorized access to a business' computer system, steal credit card data or other sensitive information and attempt to extort money from the business by threatening to release the information publicly. The unknown perpetrators "also defrauded PayPal through a scheme in which stolen credit cards were used to generate cash and to pay for computer parts purchased from vendors in the United States." U.S. Department of Justice Press Release. The investigation would reveal that the perpetrators had taken control of many computers, including the computer system owned by a Michigan school district, and used them in the PayPal fraud scheme. U.S. Department of Justice Press Release.

The FBI identified the perpetrators were Alexey Ivanov and Vasiliy Gorshkov, two young men from Chelyabinsk, Russia, and asked the Russian authorities to extradite them. Extradition is the formal process by which one country (Country A) turns a suspect over to another country (Country B) to be prosecuted for crimes committed against that country or its citizens. There is no obligation to extradite a suspect unless the two countries are parties to an extradition treaty. Since the U.S. does not have an extradition treaty with Russia, Russian authorities refused to turn Gorshkov and Ivanov over to the FBI.

Frustrated, the FBI decided to use a sting to get Gorshkov and Ivanov. The FBI created a fake computer security company called "Invita" in Seattle and invited Gorshkov and Ivanov to come to Seattle to interview for jobs with the company. Gorshkov and Ivanov eventually agreed, arriving in Seattle on November 10, 2000. They were taken to the "Invita" offices, where there were interviewed and then asked to demonstrate their hacking skills, using a test network created by the FBI. In so doing, Gorshkov and Ivanov accessed files on two computer servers located in Russia in order to obtain tools they needed to break into the test network.

What neither Gorshkov nor Ivanov knew is that the FBI had installed a keystroke logger on the computers they used to break into the test network; it recorded the usernames and passwords they used to gain access to the servers in Russia. FBI agents arrested Gorshkov and Ivanov after they broke into the test network, and then used their usernames and passwords to access the Russian servers. After conducting a complete search of the files on both servers, FBI agents downloaded 1.3 gigabytes of data. They did all of this without a warrant; the agents did obtain a search warrant before they examined the files, which were stored on computers in Seattle.

Gorshkov and Ivanov were charged with various federal crimes, including computer theft and extortion. Gorshkov moved to suppress the evidence the FBI had obtained by accessing the Russian servers, arguing that the agents' conduct violated "our" Fourth Amendment. Applying the standard outlined above, the District Court judge denied the motion, holding that the Fourth Amendment did not apply to

"the agents' extraterritorial access to computers in Russia and their copying of data contained thereon. First, the Russian computers are not protected by the Fourth Amendment because they are property of a non-resident and located outside the territory of the United States. . . . [T]he Fourth Amendment does not apply to a search or seizure of a non-resident alien's property outside the territory of the United States. In this case, the computers accessed by the agents were located in Russia, as was the data contained on those computers. . . . Until the copied data was transmitted to the United States, it was outside the territory of this country and not subject to the protections of the Fourth Amendment."

United States v. Gorshkov, 2001 WL 1024026 (W. D. Wash. 2001).

As I said, I have some general problems with the notion that "our" Fourth Amendment does not apply to real-world searches, such as when our law enforcement officers abduct someone from another country and bring them here for trial. I am willing to assume that we cannot require our law enforcement agents literally to comply with the Fourth Amendment when they are searching for evidence or suspects in another country; it would, I imagine, be impossible for them to obtain a search or arrest warrant that would meet our requirements in most other countries. But why can't they obtain a warrant from a U.S. court and then execute it abroad? The warrant would not be legally binding in the country in which the U.S. agents act, but it would ensure that their actions comport with the requirements of our law.

Our courts have never addressed this possibility because extra-territorial searches and seizures have been defined as outside our Constitution for well over a century. This definition is the product of the historical conception of sovereignty, which linked the applicability of law with one's presence in the territory of a specific sovereign. In Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893), for example, the U.S. Supreme Court said that the U.S. "constitution has no extraterritorial effect, and those who have not come lawfully within our territory cannot claim any protection from its provisions". And that approach still makes a great deal of sense; we cannot, for example, extrapolate our law outside our territory, so that we require law enforcement officers in Canada to give Miranda warnings to those whom they arrest.

The trouble with networked computer searches and seizures is that they may not occur "in" the territory of a single sovereign nation. In the Gorshkov-Ivanov case, the process the FBI agents used to obtain the data from the Russian computers involved actions that, I think, occurred in at least two nations:

- The FBI agents initiated the search and seizure from the United States, when they began the process of communicating with the Russian servers.

- Once the agents gained access to and began searching the Russian servers, their actions occurred "in" Russia.

- The agents' compiling the data they would download to their computers also occurred "in" Russia.

- The agents' initiating the download occurred "in" Russia.

- The arrival of the data on the Seattle computers occurred "in" the United States.

Situations such as this are not encompassed by the holdings of the Supreme Court cases which have held that "our" Fourth Amendment does not apply to extra-territorial searches and seizures directed at property owned by non-U.S. citizens. Those cases all addressed law enforcement activity which took place entirely in another country (except for the process of bringing evidence and/or a suspect back into the United States). They did not deal with remote searches and/or searches, because they were not possible until very recently.

I do not think the Supreme Court's extraterritorial search holdings should apply to transnational computer searches, like the one in the Gorshkov-Ivanov case. I think there are two reasons why we should treat transborder computer searches and seizures differently.

- One is that the law enforcement conduct in these searches/seizures does not take place entirely outside the territorial boundaries of the United States. Our experience with this type of activity is still in its infancy, but I think it is reasonable to assume that the default scenario will be the one we saw in the Gorshkov-Ivanov case -- a situation in which law enforcement officers launch a search/seizure from within the United States that is directed at data located in another country (or other countries). Since the officers are physically located in the United States, I think U.S. law should govern their actions. This result is consistent with the rather formulaic equation that equates the applicability of law with presence in a sovereign's territory; it is also consistent with the premise that our officers must abide by "our" law when they are in the United States.

- The other reason is that in this scenario U.S. law enforcement officers can comply with U.S. law, specifically, with the requirements of the Fourth Amendment. It may be unreasonable to require U.S. officers to obtain a U.S. search warrant before they search, say, a building in Chile in an effort to locate evidence of illegal drug-dealing; aside from anything else, the logistics involved in obtaining such a warrant have traditionally made this impracticable. If, however, the officers are physically located in the U.S., there seems to be no reason why they cannot obtain a warrant authorizing the actions they intend to take in the course of conducting a transborder computer search for evidence.

If that had been done, it might have mitigated the hard feelings that resulted from the FBI's actions in the Gorshkov-Ivanov case. In August of 2002, the Russian Federal Security Service charged one of the Invita FBI agents with hacking in violation of Russian law. The Russians in effect charged the agent with doing what Gorshkov and Ivanov had done: gaining access to computers without being authorized to do so. I've read the Russian hacking statute, and I think the charge was well-grounded. The FBI agents did not have Gorshkov's or Ivanov's permission to use their passwords to access the Russian servers; there access was, therefore, unlawful.

The Russians asked the U.S. Department of Justice to turn the agent over for prosecution, at least twice. They received no response to either request. When they were asked why they bothered, knowing the U.S. would not turn the agent over, they said they brought the charges as a symbolic gesture . . . as a way of protesting what they saw as illegal activity by the FBI.

I do not think this is any way to run a global law enforcement environment.

No comments:

Post a Comment